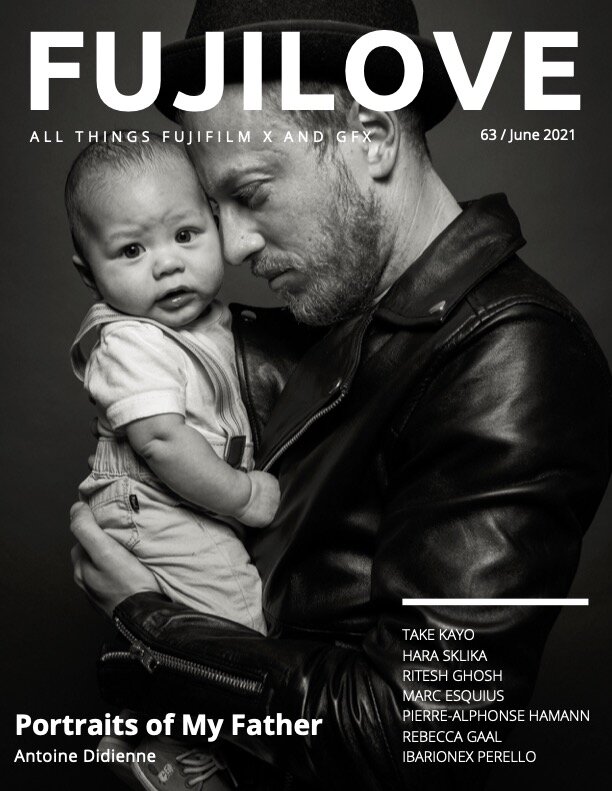

Portraits Of My Father

As a father of two and the son of one, you’d think I would know what being a father means but as Antoine, I only get to understand -barely- my own version of this human experiment even though some things are general for us all; so what does it mean to be a father?

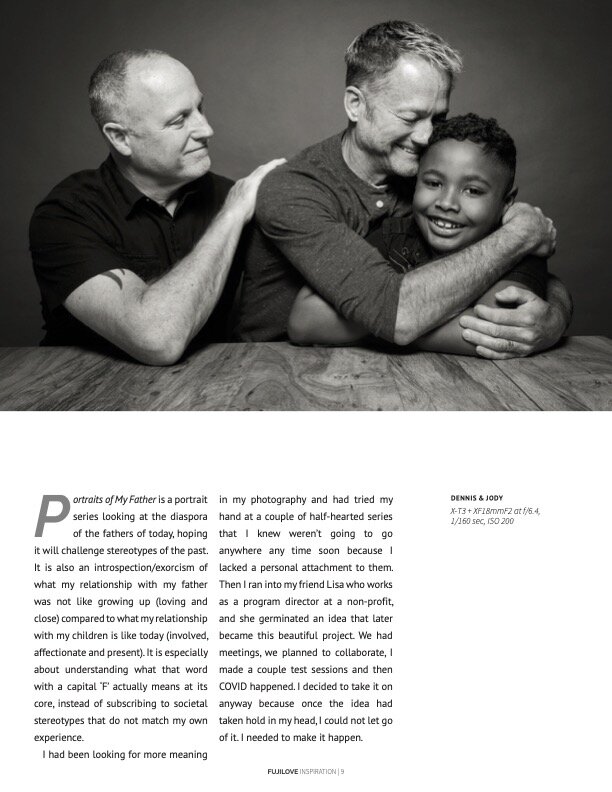

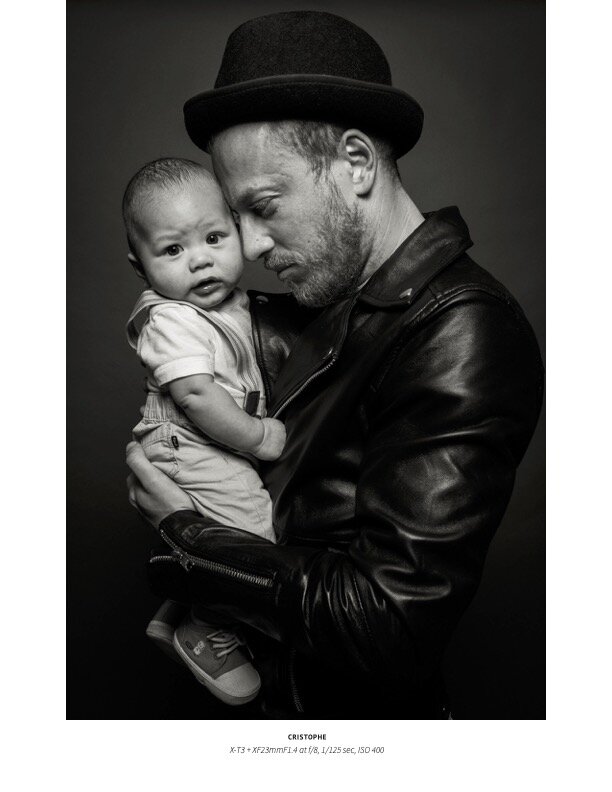

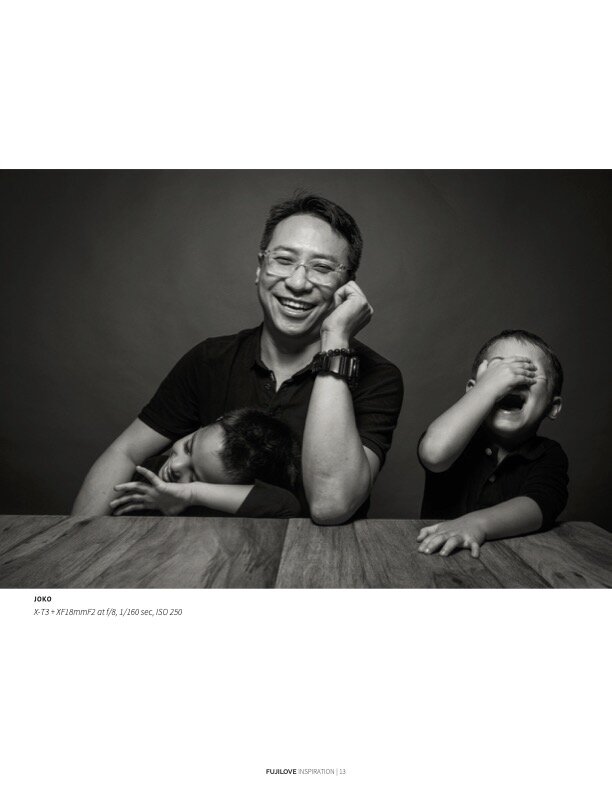

Portraits of My Father is a portrait series looking at the diaspora of the fathers of today hoping it will challenge stereotypes of the past. It is also an introspection/exorcism of what my relationship with my father was not like growing up (loving and close) compared to what my relationship with my children is like today (involved, affectionate, and present). It is especially about understanding what that word with a capital “F” actually means at its core instead of subscribing to societal stereotypes that do not match my own experience.

I had been looking for more meaning in my photography and had tried my hand at a couple of half-hearted series that I knew wasn’t ever going to go anywhere any time soon because I lacked a personal attachment to them. And then, I ran into my friend Lisa who works as a program director at a nonprofit and she germinated an idea that later became this beautiful project. We had meetings, we planned to collaborate, I made a couple of test sessions, and then... COVID happened. I decided to take it on anyway because once the idea had taken hold in my head, I could not let go of it. I needed to make it happen.

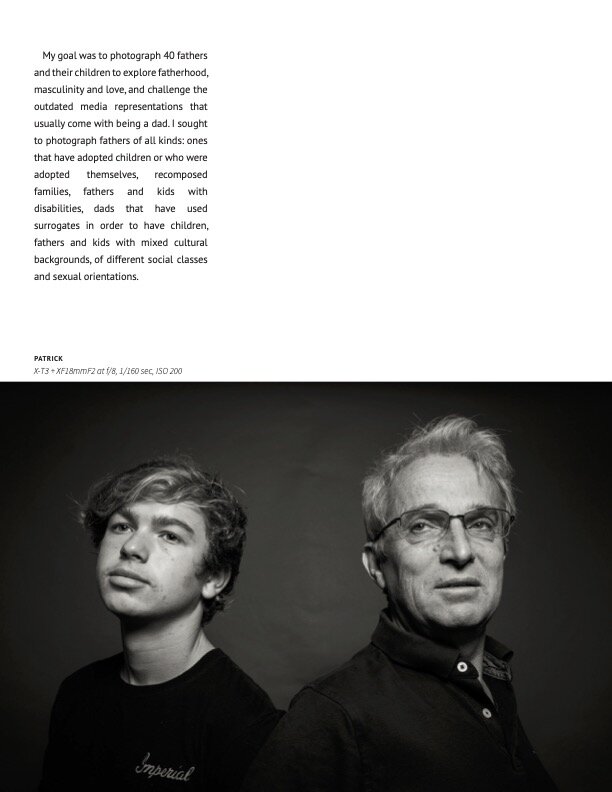

My goal was to photograph 40 fathers and their children to explore fatherhood, masculinity, love, and challenge the outdated media representations that usually come with being a dad. I sought to photograph fathers of all kinds: Ones that have adopted children or who were adopted themselves; recomposed families; fathers and kids with special needs; dads that have used surrogates in order to have children; fathers and kids with mixed cultural backgrounds; of different social classes and sexual orientations...

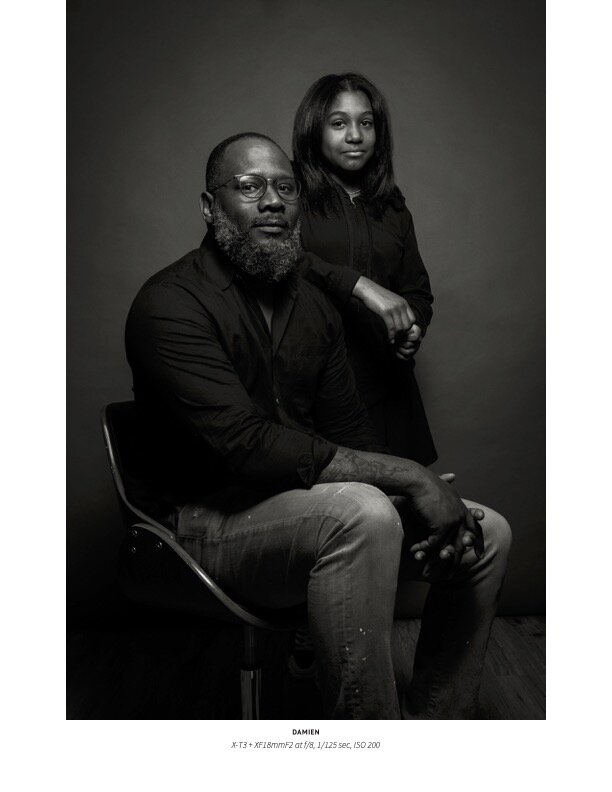

Honestly, the hard part wasn’t finding the fathers but coming up with a title for this project. It took me about eight months to come up with the very simple and evocative Portraits Of My father. The doing of the project was so important to me that titling it seemed trivial, even if I knew it was an important piece of the puzzle. When I figured out the title, that’s when I realized I was doing this project to justify my own experience as a father, to exorcise my resentments as the son of a somewhat absent father, and to prove that fatherhood is as wide a human experience as there are human beings. Photographing 40 fathers seemed like an ambitious number at the time. A year and a half into this project and that number feel inconsequential now, like I’ve barely scratched the surface.

Fatherhood is such a heavily loaded word. Fathering a child and being a father are two different things altogether. Being a good father is hard-- it’s like an old-school oath. It’s a project you are committed to working on for the rest of your life, and I don’t care how many books you read about parenting, you can only learn to be a father once you become one. All these rules and ideas you think you have about what you’ll do as a father because you’ll never repeat the mistakes your dad made is a good start, but it’s just that: a place to launch from.

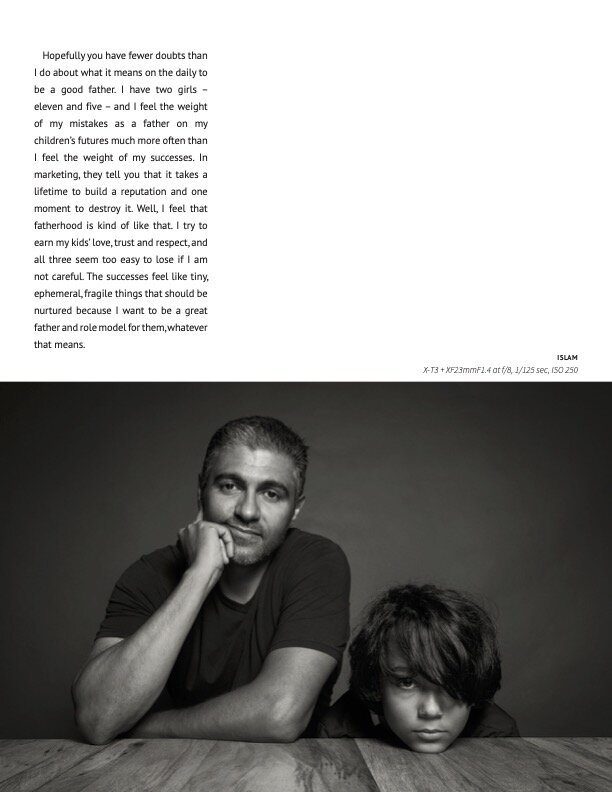

Hopefully, you have fewer doubts than I do about what it means on a daily to be a good father. I have two girls -11 and 5- and I feel the weight of my mistakes as a father on my children’s futures much more often than I feel the weight of my successes. In marketing, they tell you that it takes a lifetime to build a reputation and one moment to destroy it. Well, I feel that fatherhood is kind of like that. I try to earn my kids’ love, trust, and respect and all three seem too easy to lose if I am not careful. The successes feel like tiny, ephemeral, fragile things that should be nurtured because I want to be a great father and role model for them, whatever that means.

Having two daughters and watching them grow up made me realize many things about fatherhood and I’ve relaxed a lot over the years about what we as a society think fatherhood looks like. Men are still mostly viewed as financial providers for their families with little emotional bandwidth. Our roles are changing rapidly but I’ve judged and compared myself to other -better?- fathers that seemed to have their stuff together and seemed to do it “right.” I’ve felt guilty because I was a stay-at-home parent and I’ve felt guilty because I was working… sometimes during the same day. I am a very progressive person but I have demeaned myself because I was “just” a stay-at-home dad. In the back of my mind, I could not shake the indoctrination of my father’s generation that as a husband, I should be out there providing for my family. The media still portrays dads very involved in their kids’ lives as heroes instead of something that is normal. It took me a while to separate my father’s experience from my own and to get over my shame and guilt over what I thought my responsibilities were. I am a grown man and fairly introspective; and yet it took me a long time to really understand what my role as a father was.

It’s weird how taking pictures of others can be therapeutic and healing for my own traumas. These images are as much about the fathers in the picture as they are reflections of my experience as a father and a son. This ode to fatherhood helped me to take stock of my own mistakes, shortcomings, but especially of my own successes as a father. The weirdest part of it all to me is that I also became closer to my father somehow without ever talking to him about all this. I let go of some things and made peace with others. I felt I could understand him better. I came to terms with enjoying the relationship I have with him instead of resenting him for the one I wanted to have. And what I have come to truly realize since starting this project is that DNA doesn't mean much when it comes to being a father. It’s just about the love we give to our kids and what we do with that love. Being a good father is truly a respectable thing to be. What a discovery, right?